In recent years, across Asia, the number of programs at the university level that teach English through content has been increasing. With Content Based Instruction (CBI), the subject matter becomes the vehicle by which language is learned. Proponents of CBI claim many benefits. For example, CBI is said to be more motivating in that it provides students with real-life experiences in using the target language. Furthermore, it is claimed, learning is more fun and interesting, as students can use the target language as a tool to learn new things, which is thought to be a more natural way to learn a foreign language.

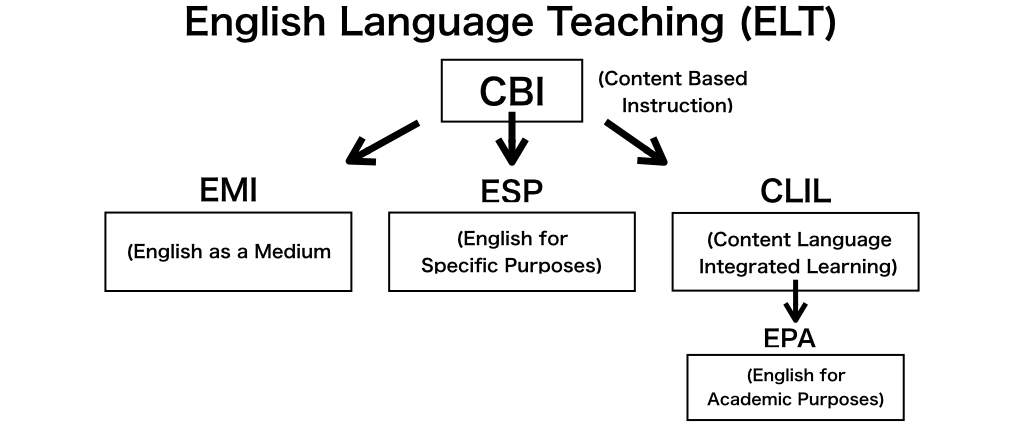

However, as there are many pedagogies associated with CBI, these need to be clearly defined. English Language Teaching (ELT), like many fields, is awash with acronyms. However, each acronym brings with it sets of assumptions that need to be well understood.

Let’s start with the main three acronyms associated with CBI: EMI, CLIL and ESP. Basically, the major differences between these approaches is the amount of linguistic support that is offered concurrently.

EMI stands for English as a Medium of Instruction. In EMI classes, content is delivered in English and feature no linguistic focus on form. EMI is more focused on content learning. With EMI classes, policy makers assume that students will develop their English proficiency as an incidental and felicitous by-product of having classes in English. That is, language learning itself is largely left to develop on its own. Tests and evaluation typically limit their focus to testing how much of the content has been learned.

CLIL stands for Content Language Integrated Learning, and CLIL classes have a dual purpose: the learning of language and the learning of content. In such classes, linguistic support is assumed to be needed.

ESP stands for English for Specific Purposes, and, like CLIL, it also has a dual purpose of learning both language and content. ESP, as an acronym, has been around much longer than CLIL, and the differences between ESP and CLIL are often debated. Typically ESP classes are regarded as having more of a focus on linguistic form than CLIL.

So, a central assumption of all EMI classes is that students can, for the most part, comprehend academic lectures. If we were to reference the CEFR framework, this suggests that students need to have a minimum proficiency level of B2 to take part in such classes, which in reality is far above the proficiency of all but a few students in Japan.

In fact, for reasons outlined on page 3, most Japanese struggle to comprehend naturally spoken English. Most students face the problem of not being able to listen and comprehend words that they know! That is, they have difficulty understanding spoken language that they would easily understand were it written. So expecting our students to comprehend academic lectures is often unrealistic.

English, unlike most Asian languages, reduces substantially in connected speech. Unstressed syllables that come between stressed syllables tend to be highly reduced. In European contexts, phonological interference might not be such an important consideration, because most European languages are stressed timed and generally match the phonological rhythms of English.

If there are phonological impediments that need to be overcome, this suggests that policy makers in Asian contexts might be better off implementing CLIL classes or ESP/EAP classes that have as a core a focus on linguistic form to help students better understand the content.

In short, our students need more support, more detailed instruction and more practice to comprehend naturally enunciated English. While CBI has many merits, in Japan, CLIL and ESP seem like the much better choice.

Comments(0)

Leave a message here