Extensive reading has been a required component in the core curriculum for first- and second-year students for the past six years at my university. Once students understand what extensive reading is, many of them start with very easy, familiar stories such as fairy tales, Disney stories or early readers meant for children. They might then move on to popular books from films such as Men in Black, The Devil Wears Prada, Sex and the City, and the like. This is a good place to start for learners right out of high school who have never really read in English for the sake of enjoyment or had exposure to these sorts of books. We encourage our students to read within their level and also to explore outside of their comfort zone in terms of genre. For example, we often recommend juvenile fiction chapter books such as the A-Z Mysteries or the Magic Tree House series, or non-fiction global issues-type readers to get a sense of some of the problems affecting the wider world. We have had success with the former but not as much with the latter. Many find that the books which address global or social issues tend to be too ‘study-oriented’ or as one student put it, ‘too dry, no story, not interesting’. Save for a small handful of readers in this genre such as Jojo’s Story (Antoinette Moses) and Rabbit-proof Fence (Doris Pilkington Garimara and retold by Jennifer Bassett) in our 15,000 strong ER library, we would be inclined to agree.

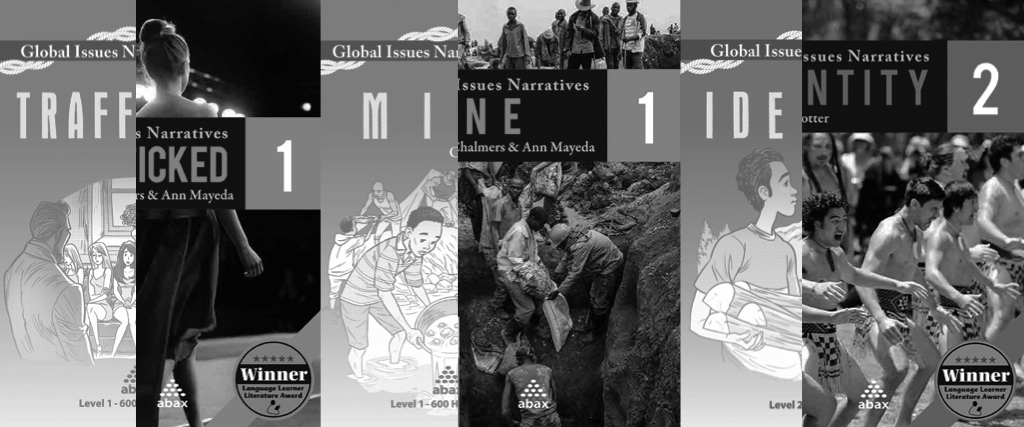

We have found that the narrative format at a lower level (A2, 600-1,000 headwords) seems to be very popular. Stories keep students interested and coming back for more. With this in mind, Catriona Chalmers and I have embarked on a quest to deliver global-issues themed low level graded readers with strong storylines. Our aim is to tell fleshed-out stories on complex issues using accessible language. So how do we incorporate perspectives and thought-provoking ideas so that our learners can experience views that may differ from their own?

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie stated in her now famous TED talk, The Danger of a Single Story (2009):

“The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.”

We can show greater complexity when we reject the notion of one story and accept a series of alternative voices and experiences. The key is easy language driven by the strong narrative of each voice. For example, in Trafficked (http://www.abax.co.jp/

Some of these stories have been piloted in our classrooms and it has been eye-opening to see how learners will ‘own’ their character’s viewpoint until they start to hear another voice and then another. The discussions that follow have given us renewed faith in the power of learning language and content with graded readers. While these issues may seem far removed from the lives of our students, we hope that they can begin to understand how all of our lives are intertwined in our interdependent world.

Comments(0)

Leave a message here